Far From The Pictures: Mireille Blanc

Past exhibition

Press release

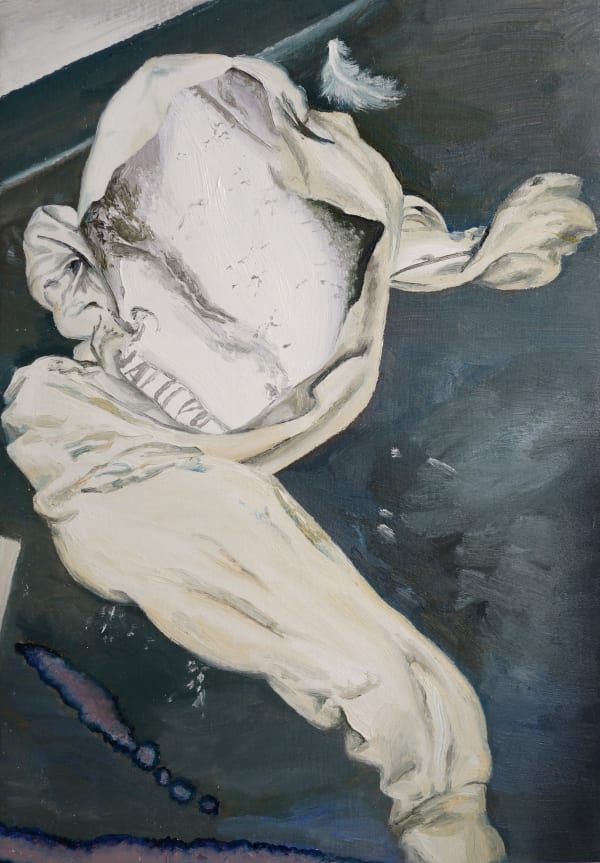

For her new exhibition, Mireille Blanc proposes to take us far from the pictures. Paradoxically, the artist presents us with figurative paintings at THE PILL Gallery's space in Istanbul. The eye can't help but recognize fragments of a disorderly interior: an empty yoghurt pot lies overturned, a sweatshirt rests carelessly on the ground, a forgotten Popsicle melts on a plate... The rendering of the images bears witness to a similar license. There are smudges, discolorations and blurred effects. One senses a rapid, unrestrained painterly gesture, with little concern for meticulously reproducing the real. An emancipated way of making, in keeping with the casual subject matters.

In discussing Mireille Blanc's work, it is often said that photography serves as the premise for her paintings. Close-up shots, often taken quickly with her iPhone, guide the painting process in the studio. But beyond this specific metholodolgy, photography also provides a glimpse into the life of the artist, who is unafraid of the commonplace. These snapshots take us into her kitchen, to a waiting line, in front of a school diary. While overtly rooted in the domestic sphere and family life, her work is just as much about art history, as indicated by the image of the plate number 2 from Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas which welcomes the visitors at the entrance of the exhibition. The Atlas, in which the German historian combined thousands of illustrations in the 1920s, ushered in a new form of visual investigation that some consider a true epistemological breakthrough. Following in Warburg’s footsteps, Mireille Blanc uses photographic images as the starting point for works in which seeing becomes knowing.

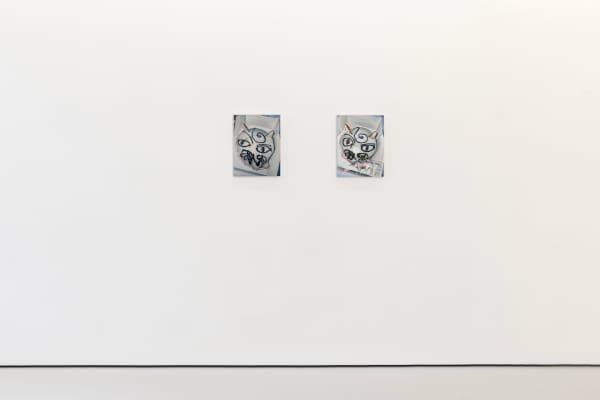

It is in this back-and-forth between the grand and the so-called small history that Mireille Blanc forges her path as an artist, without evacuating her role as a mother and her identity as a woman. Hints of her family life are indeed very much present - plasticine games, birthday cakes, … - but the most obvious painting regarding her gender identity is undoubtedly “Emporte-pièce (l'avion)” where, as the title suggests, a kitchen tool is unexpectedly placed on the tonsure of a female genitalia. The ornate shape of the plane, reminiscent of the female reproductive apparatus, seems to imbue the flesh of the naked body. In this image, gender appears in the form of a mold deliberately placed on a physical attribute, and it is unclear whether the finger holding the cookie cutter is that of a third party or of the artist herself, who, through this gesture, incorporates social gender norms. In a more childlike but no less significant vein, the small plasticine sculpture in the painting “Dog” reminds us how matter is molded to become form. The "cats" depicted are just as factitious, since they are decorated cakes. In this case, it's the topping that transforms, in a rudimentary yet absolute manner, the way we perceive what we're shown.

The pastries, fruits and candies that abound in the exhibition evoke indulgence and pleasure. The painting “Croissant”, which belongs to this iconographic family, once again relates to the canonical art history, as it is reminiscent of one of the brioches painted by Edouard Manet. In his 1880 “Nature morte à la brioche”, now in the collections of the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh, the pastry placed on a blue plate at the heart of the composition, just as in Mireille Blanc's painting, looks astonishingly like a male sexual organ at rest. There's an eroticism in this work that we find in a contemporary and feminized version in Mireille Blanc's work, where the sophistication of traditional French pastry is now giving way to more industrial, artificial pleasures, with packaging and colorants.

A similar sensuality runs through the images of sweatshirts, another recurring motif for the artist. Much like Wolfgang Tillmans' photographs which show carelessly abandoned clothes, as if after a hasty undressing, the painted garments evoke absent bodies and carnal pleasures. These fabrics are also mediums for words and images, where the history of painting can once again be inscribed. The tracksuit in “Tournesols”, for example, features a well-known painting by Vincent Van Gogh, first reproduced on merchandising, then photographed on the sly by Mireille Blanc and finally repainted in her studio, following a logic of repetition reminiscent of the “Refrain” programmatically placed at the entrance to THE PILL gallery, alongside the reference to Aby Warburg described above.

Paradoxically, it is thus through repetition that Mireille Blanc distances herself from images. Firstly, by the distancing of painting, which proclaims its autonomy from the photographic reproduction of reality. Secondly, and above all, through the singular way through which the artist looks at the everyday. To the well-ordered life of patriarchal family, she contrasts her freedom and autonomy, which pervade both her technique and her choice of subjects. Instead of perfect images, the artist confronts us with sensations, impressions, gestures, and embodied flesh. Mireille Blanc does not seek to create illusion.

Devrim Bayar

Installation Views

Works

-

Mireille Blanc, Chat 1, 2022

Mireille Blanc, Chat 1, 2022 -

Mireille Blanc, Chat 2, 2022

Mireille Blanc, Chat 2, 2022 -

Mireille Blanc, Dog, 2022

Mireille Blanc, Dog, 2022 -

Mireille Blanc, Croissant, 2023

Mireille Blanc, Croissant, 2023 -

Mireille Blanc, Emporte-pièce (l'avion), 2023

Mireille Blanc, Emporte-pièce (l'avion), 2023 -

Mireille Blanc, Goûter, 2022

Mireille Blanc, Goûter, 2022 -

Mireille Blanc, Iris, 2023

Mireille Blanc, Iris, 2023 -

Mireille Blanc, Pavlova Zouzou, 2021

Mireille Blanc, Pavlova Zouzou, 2021 -

Mireille Blanc, Photo, 2023

Mireille Blanc, Photo, 2023 -

Mireille Blanc, Planche 2 - A.W., 2018

Mireille Blanc, Planche 2 - A.W., 2018 -

Mireille Blanc, Refrain, 2023

Mireille Blanc, Refrain, 2023 -

Mireille Blanc, Sweat, 2023

Mireille Blanc, Sweat, 2023 -

Mireille Blanc, Tournesols, 2022

Mireille Blanc, Tournesols, 2022 -

Mireille Blanc, Yet, 2023

Mireille Blanc, Yet, 2023

Exhibition Text

Far From The Pictures

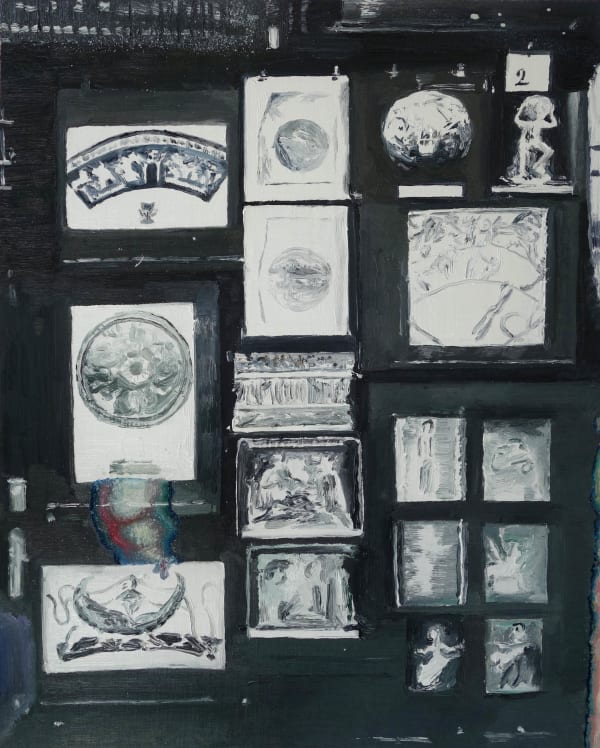

THE PILL is delighted to announce Mireille Blanc's second solo exhibition at the gallery from 8 May to 14 June. Entitled Far From the Pictures, it features a group of recent paintings emblematic of the relationship her painting establishes with images. These works form an arborescence that begins with one of the artist's iconic paintings, Planche 2 - A.W., placed at the entrance to the exhibition and which can be read as an essential key to an overall understanding of Mireille Blanc's work.

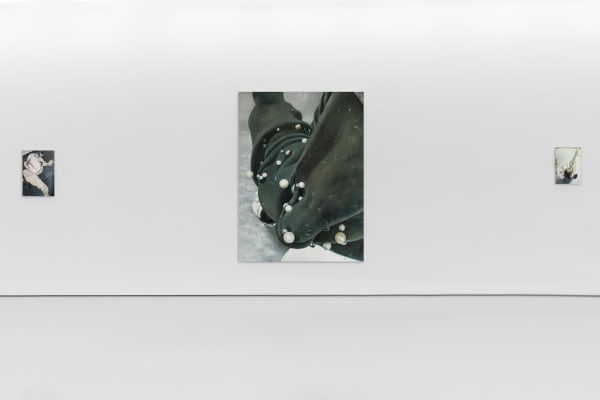

Drawing on subjects borrowed from the familiar and family contexts - cakes, leftovers from children's meals or snacks, modeling clay figurines, school exercise books, etc. - the paintings reveal a wealth of cracks, small imperfections, stains, and chromatic effusions that distort the image and contribute to the foundation of the painting. The false pieces of tape that sometimes appear discreetly around the edges, or the colored smudges that dot the surface, provide information about the process and the origin of these paintings. In fact, they were not painted on the motif or from memory, but from photographs, with the difference that the aim here is not to reproduce the image fixed on the photograph but the photograph itself (the sheet of photographic paper) with its imperfections, stains and discolorations caused by accident during handling in the studio. A painting by Mireille Blanc is therefore the reproduction of a reproduction of an image: the subject is placed at a double distance, the images move away and the painting emerges, far from the pictures.

This representation of the photographic object, redoubled by the creaminess of the brushstroke, is a way of asserting that a painting is not an image but a surface, in order to emphasize the painting's perfect autonomy with respect to its subject. It's a question of giving painting a new body vis-à-vis images by using a creamy surface - with all the irony of certain 'creamy' paintings representing cream cakes - to bring a form of stridency to the transition from the flat image of photography to the creaminess of the pictorial touch. It is also a question of underlining the memorial role of painting in relation to photography, of showing how the painting of an image opens up the field of sensation and memory beyond the possibilities specific to photographic images. Add to this a further consideration that what is at stake in these paintings is not the reproduction of the photograph but its repetition. Reproducing and repeating are two very different acts. Repetition is not reproduction, it always contains a transformation. To repeat is to modify by moving forward, to remember is to modify by moving backward. As Søren Kierkegaard put it, "repetition and remembrance represent the same movement, but in opposite directions".

The exhibition opens with Planche 2 - A.W., juxtaposing barely legible images against a black background, revealing sketches of bodies and circular geometric shapes that evoke spheres, globes; or ornamental panels. The painting is executed in shades of gray, except for a few whites tinted with yellow, bisters and greens. The surface is marred by a multicolored stain and a chromatic effusion that eats away at the right-hand edge of the painting. This detail is important because it provides information about the photographic origin of this painting: it is a reproduction of a picture that was damaged by water or humidity. A clue is provided by the initials "A.W." in the title of the work: they are those of the famous iconological historian Aby Warburg, and Plate 2 - A.W. is inspired by his Mnemosyne Atlas, an immense iconographic work in progress that he conceived between 1927 and 1929 in a decisive move to overhaul the principles of the discipline of History. Aby Warburg sought to rediscover the links that secretly seemed to unite distant eras and cultures by examining their images. His famous plates, which first illustrated his lectures before becoming autonomous forms on display in the immense library of over 60,000 works that he established, are direct evidence of his concept of the iconology of the interval ("Ikonologie der Zwischen Raums"): with Aby Warburg, images can now be understood differently, on the basis of their analogies, their frictions, and their unexpected connections. As Jean-Luc Godard pointed out: "There is no image, there are only images. And there is a certain form of assemblage of images [...] There is no image, there are only relationships of images". Nevertheless, the heart of Aby Warburg's enterprise lies not so much in an archive of interconnected images as in the new way he looks at the gestures these images reveal. In the final analysis, his project did not consist in studying images, but rather in examining how a particular type of gesture traveled through time, from era to era, from culture to culture, thus highlighting the existence of a gestural system fundamental to human civilization, which could then become a particular prism through which to view the history of humanity.

Plate 2 - A.W. opens and closes Mireille Blanc's exhibition. The choice of this iconic painting within her oeuvre provides an essential understanding of her practice. Plate 2 - A.W. is not a representation of the plate from the Mnemosyne Atlas, but rather a representation of a photograph from this plate, which is itself made up of an assemblage of photographs. The disparate images that make up the Mnemosyne plate are thus unified in a single image. It's a fine synthesis of the risk of anachronism to which we are subjected when we look to the past, always perceived from the point of view of a present that operates an optical diffraction doubled with trouble. The symptom is there, in the gradual loss of definition of the images as they are transposed, so that in the end all that remains are gestures of painting inhabited by the ghostly return of all the pictorial gestures of the history of art. Placed at the entrance and exit of the exhibition, Planche 2 - A.W. opens and closes an arborescence of paintings with interconnected motifs, revealing their gestures in an iconological process similar to that used by Aby Warburg to compose his plates. Plate 2 - A.W. dialogues with Refrain's childish gesture of school writing in relation to ritornello, to the repetition of words, gestures, and images. It connects with Dog and its agglomerate of modeling clay, its jigsaw puzzle of disparate elements modeled by hand to create a sculpture, then an image, and then the sum of painted gestures. The rest of the exhibition is a succession of rebounds, motif after motif, from the most identifiable subjects to representations rendered ambiguous by contradictory compositions and gestures. Goûter and Emporte-pièce refer to puncturing, cutting, and hybridity, in a kind of Frankensteinian gesture that rubs up against the little canine monster made of modeling clay with which these two paintings dialogue in perspective. In the end, the images are summoned to beat in retreat to leave the field open to painting. Far from the pictures.