Salad Cake : İrem Günaydın

Passé exhibition

Communiqué de presse

A Love of Hors d’Oeuvres

Aslı Seven

Almost exactly one year before this exhibition, there was a late night conversation between Irem and I. We were sitting on one of the long tables arranged in the studio of Leyla Gediz: it was a New Year’s feast-party. People surrounded us, there was food in front of us, our glasses were full and we talked in length about the concept of “Parergon”. The word comes from Greek, merging of “para-” and “ergon”, it designates all that is beside, in addition to, or outside “the work of art”. While it may simply refer to the frame or the ornamental elements, in Derrida’s thought it expands to include the artwork’s negative space and its borders, as that which simultaneously stabilizes and sets in motion the work of art. In French, the exact translation would be “Hors d’Oeuvre”, universally known as the culinary term for small portions of food served outside the main course - often to encourage a guest to drink more.

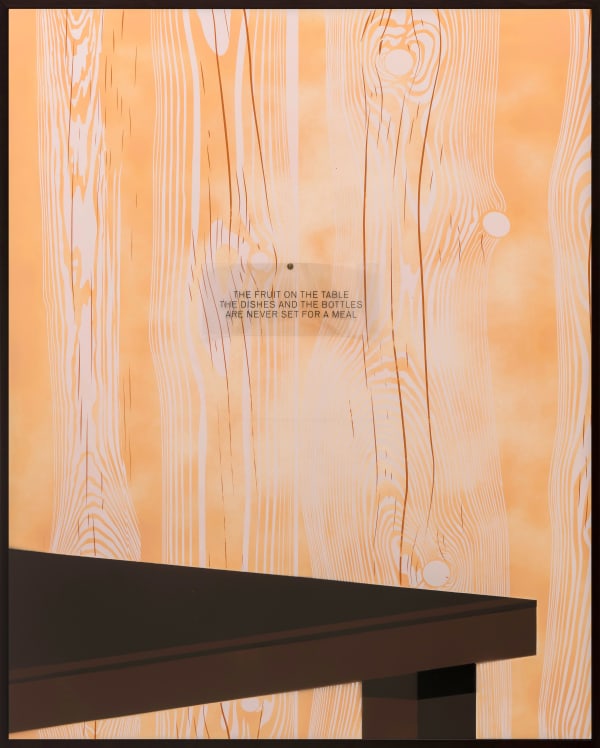

A year later we are at THE PILL®, in an exhibition titled “Salad Cake”, standing before a video installation. The camera moves back and forth between fruits and vegetables scattered across a table, all in close up views. A voiceover, the artist’s voice mixed with the voice of Morpheus from the Matrix and a male voice speaking English with a French accent, recount a story about four art historical characters confronting the truth of painting and a choice between the “dreamworld” and the “desert of the real”, which turns out not to be a choice, but rather a provocation to fold them together. A letter, from herself as an artist about herself as a non-artist. And then there are vertical views of cooking gestures: separating egg yolks on one and macerating berries on the other. I keep thinking that in an invisible way, what frames them all together is the studio of Leyla Gediz (A painter’s studio) once again, where Irem produced this exhibition, where we saw each other last summer. A painter’s table constitutes the ground upon which these fruits and vegetables are scattered. Both outside and inside Irem’s works. What we have here is a whimsical play across mediums, weaving art into non-art and back into art again.

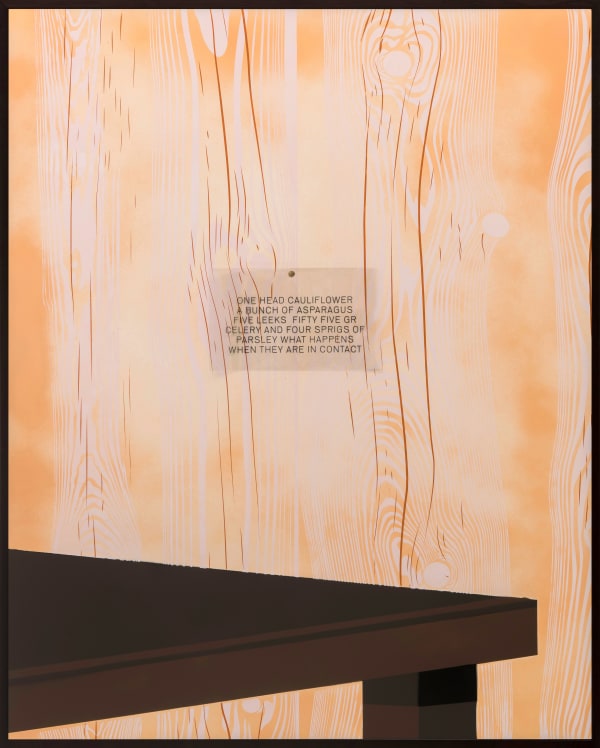

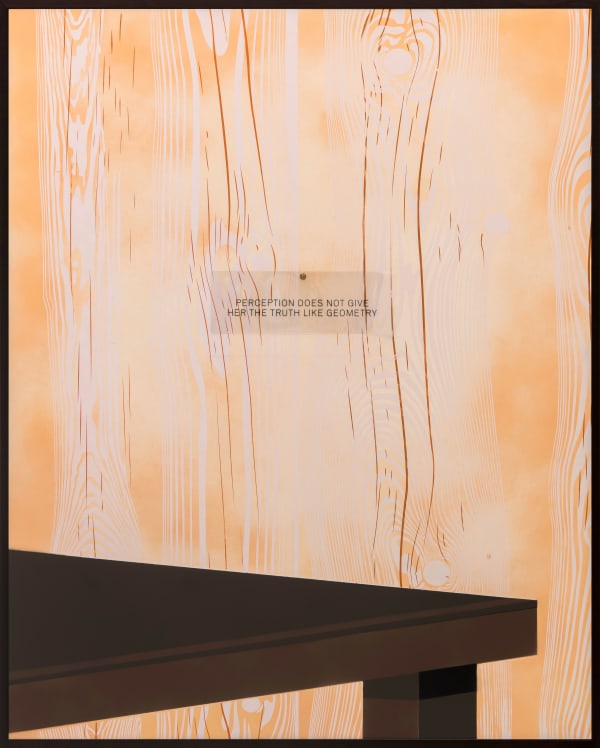

Irem Gunaydin is interested in the conditions of possibility of art making. This is another way of stating that she is interested in the frame and the ground rather than the image-as-representation; in what happens between context and canon, between work and frame on one hand, between process and oeuvre, on the other. She is also interested in perforating the tightly knit textures of art history and the matter of her own identity as an artist. The former, she does by diving deep into art historical canon with a focus on categories of still life and landscape, of naturalism and baroque – dissolving these categories themselves in an exploration of the plasticity of their subject matter and material conditions indistinctly. The latter, she does with a form of address most subjective yet grounded in the everyday: the epistolary form.

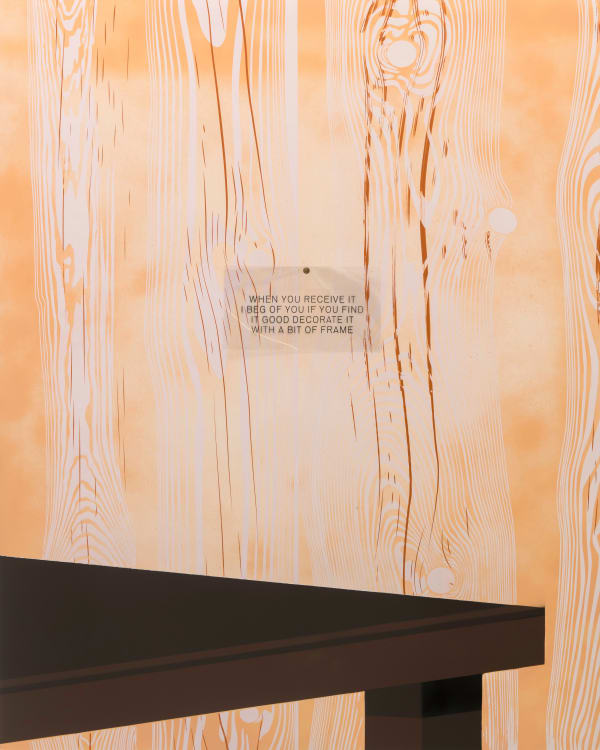

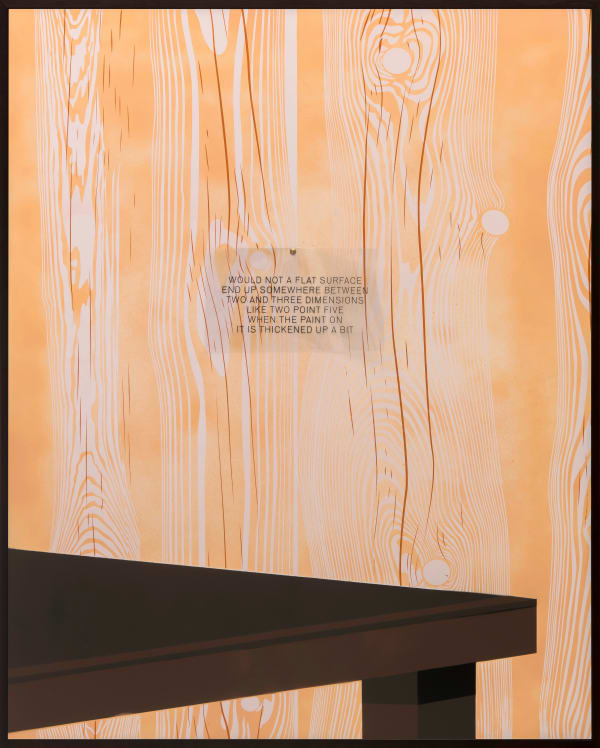

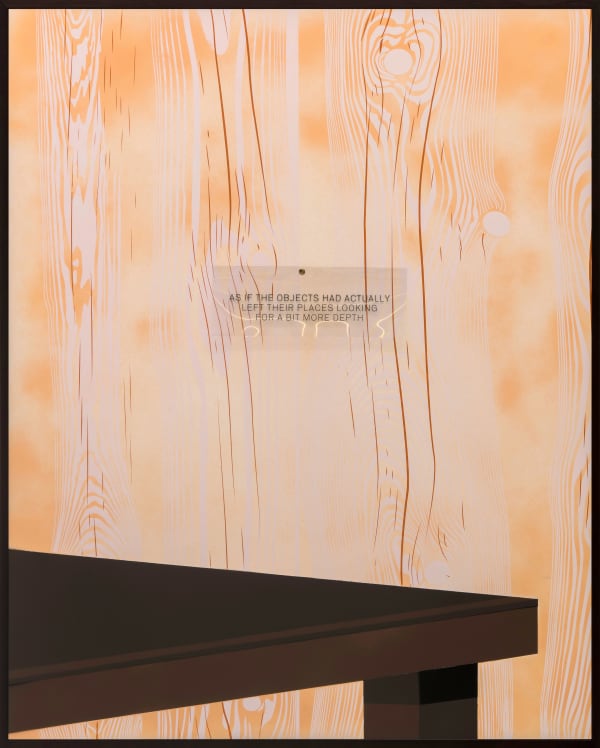

A text titled “Flaschenpost: I Owe You The Truth in Painting and I Will Tell It To You”, written by the artist, acts as a pass-partout throughout the exhibition. The latter part of the sentence is borrowed from a correspondence between two painters, Paul Cézanne and Emile Bernard, Cézanne being the one uttering the sentence and confessing a debt of truth in painting. A debt later taken up by Jacques Derrida to reflect on the same subject matter in an eponymously titled book, a debt which, now, Irem seems to take up in her own letter, adding one word to the sentence: Flaschenpost. It means “message in a bottle”, in german. So, it isn’t just the epistolary form connecting Irem Gunaydin in a conversation with Cézanne and Derrida, and connecting us as readers to all of them in a confessional mode of address, but also the idea of a distance in time and space, which is operative here. The medium is the message, and in this case its truth lies in declaring the uncertainty of its reception: when, where, by whom? How long the distance, what is the fold in time? This idea of an unstable yet undeniable distance, along with those of distinction and composition are central to the exhibition: between artist and audience, between self and shadow; between figure and background, subject matter and frame, mask and face, between the surface of the painting and the grid of the canvas.

This becomes clearer through Irem’s folding of art history outside in, using the margins to destabilize the center, scratching the elitism of high art with eruptions of the everyday and the popular. Three canonical figures, Poussin, Cézanne and Magritte appear as characters in her narrative, confronting the question of which pill to choose in Matrix: red or blue? Irem’s response is not to choose, but to “fold” in different ways, to arrive at constellations of red and blue. Similarly, the Judgment of Paris, one of the most depicted Greek mythological scenes since Renaissance, is no longer a matter of choosing between Hera, Aphrodite and Athena, but a problem of juxtaposing beats during a DJ’s gig, of varying the emphasis to achieve varying effects.

And then, there is the repetitive doubling of Irem herself: Irem the artist and Irem the currency exchange officer, dancing with each other in a shifting geometry of figure and background. They constitute each other’s subconscious, never knowing each other completely. They appear contradictory, but they are complementary, pushed together and pulled apart by gravitational forces. We are at once confronted with the economic reality of life as an artist and the problem of recognition of art making as labor: back to conditions of possibility of art making.

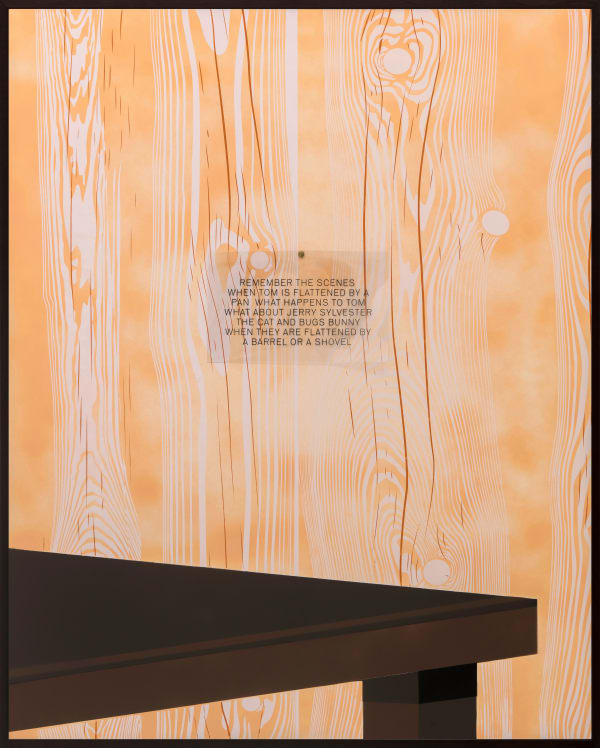

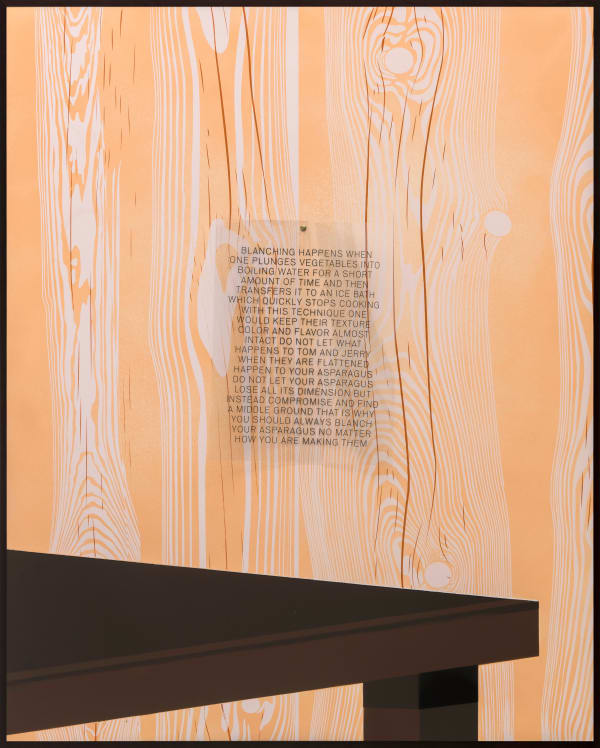

In her imaginary dialogues, Irem has a tongue-in-cheek way of interweaving threads of art historical canon with anecdotal knowledge from and around major art historical figures and themes, entangling them with visual references from 20th century popular culture – Bugs Bunny as the animated figure piercing the fabric of film, or Sylvester the Cat’s ease at shifting between dimensions. Thus arriving at a punctured texture that allows space for movement, breath and potentialities in multiple directions. In Derridean terms, we would speak of subjectile, an eruption of the ground through the figure, a protrusion of art by its outside. Circling back to the message in the bottle, what Irem’s letter and videos lay bare is the open space between the letter’s externalization and its arrival at destination where the speculative and the teleological processes of signification coexist, without the necessity of correspondence.

Vues de l'exposition

Œuvres

-

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals VIII, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals VIII, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals VI, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals VI, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals VII, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals VII, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals V, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals V, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals IV, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals IV, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals III, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals III, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals II, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals II, 2020 -

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals I, 2020

İrem Günaydın, The Integrals I, 2020