The Colour Out of Space

Passé exhibition

Vues de l'exposition

Œuvres

-

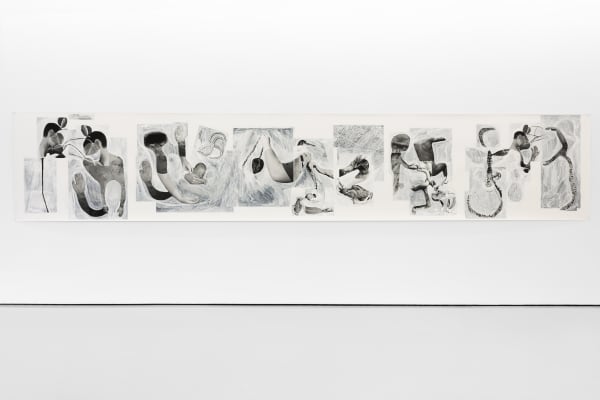

Özlem Altın, Translucent shield (calling), 2022

Özlem Altın, Translucent shield (calling), 2022 -

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting V, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting V, 2021 -

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting II, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting II, 2021 -

Jean-Charles Eustache, A38, 2023

Jean-Charles Eustache, A38, 2023 -

Jean-Charles Eustache, A50, 2024

Jean-Charles Eustache, A50, 2024 -

Jean-Charles Eustache, A49, 2024

Jean-Charles Eustache, A49, 2024 -

Jean-Charles Eustache, A47, 2024

Jean-Charles Eustache, A47, 2024 -

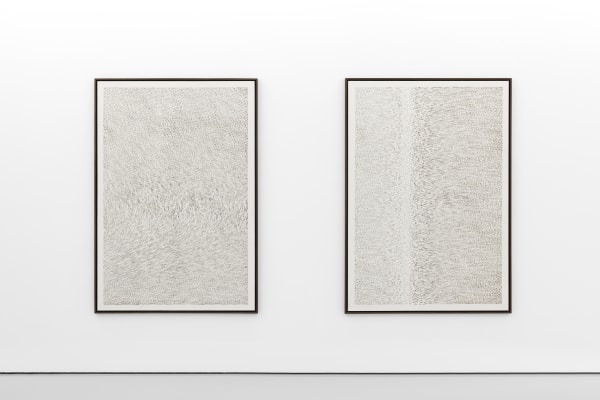

Claire Chesnier, 191023, 2023

Claire Chesnier, 191023, 2023 -

Claire Chesnier, 160323, 2023

Claire Chesnier, 160323, 2023 -

Claire Chesnier, 171023, 2023

Claire Chesnier, 171023, 2023 -

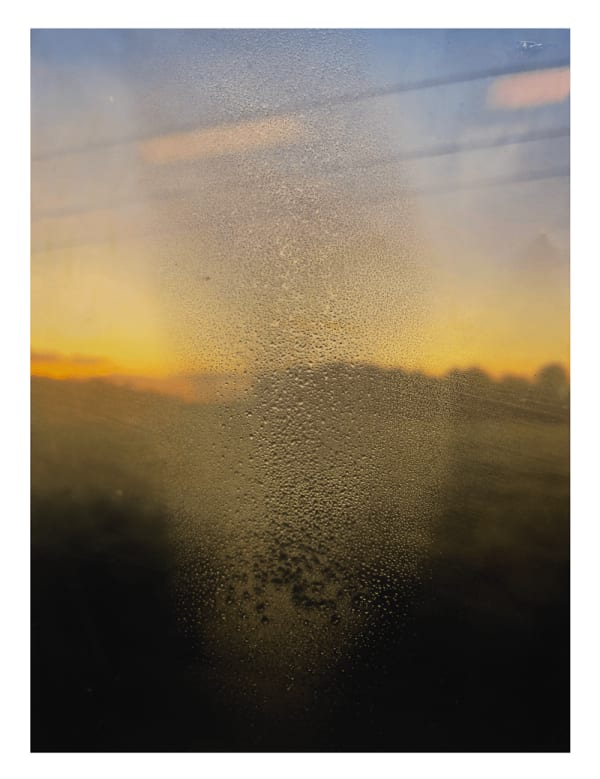

Eva Nielsen, Insolare IV, 2023

Eva Nielsen, Insolare IV, 2023 -

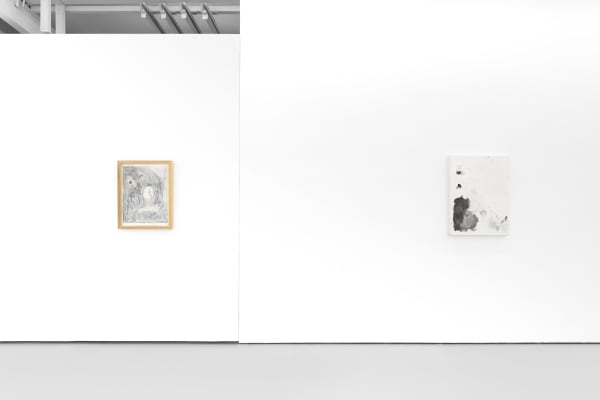

Leylâ Gediz, Palette III, 2021

Leylâ Gediz, Palette III, 2021 -

Elif Erkan, In Bloom, 2023

Elif Erkan, In Bloom, 2023 -

Elsa Sahal, Leda Texachigan, 2015

Elsa Sahal, Leda Texachigan, 2015 -

Elsa Sahal, Leda Montana 2

Elsa Sahal, Leda Montana 2

Exhibition Text

« The color, which resembled some of the bands of the meteor’s strange spectrum, was almost impossible to describe; and it was only by analogy that they named it a color after all. »

H.P. Lovecraft, The Colour Out of Space, 1927.

In his famous short story, The Colour Out of Space, published in 1927, American writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft describes the extraordinary phenomena that occurred on an isolated farm in 1882. A white cloud at high noon, a series of explosions in the air, precede the fall of a meteorite that reveals at its heart an unknown colour, impossible to define. Unnameable. The stone from the farthest reaches of outer space inexplicably contracts in its crater, transforms itself, attracts lightning. The flora becomes luxuriant before turning corrupt and crumbling into a grayish powder. Beasts and men suffer the influence of this inexpressible colour which, in a few months, inexorably transforms the landscape into a « lightning land » before suddenly propelling itself into the firmament to disappear forever, leaving behind a desolation similar to that of valleys whose tones have been undermined by the ashes of a volcanic explosion.

In the novella, color is, in the most literal sense, « the place where our brain and the universe meet », as Paul Cézanne said, underlining the deeply moving intimacy between colour and the eye. Beyond its fantastic register, The Colour Out of Space is the story of an encounter between a chromatic precipitate projected from the universe’s diffuse horizon and its fascinated, unthinkable - and ultimately cataclysmic - perception by those it touches, irreparably altering them. The title of the short story captures the ambivalence of this unholy hue exhaled from the heart of the meteorite: it falls from interstellar space, but at the same time, it is out of space. It creates space in an impalpable power, the extent of which the eye can measure, but which words cannot grasp, except in an approximate way. Colour is always stronger than language. Encountering a colour is an event in itself - we’ve all experienced it, fascinated by the dusky purple of a sky, the soft green of a meadow or the elusive iridescent modulation of a gaze. This event, staggering in its emergence, is nonetheless impossible to grasp. By establishing formal links and spatial connections between the works, this exhibition crosses the major themes of Lovecraft’s short story - unnameable colors, cosmic and earthly spaces, metamorphosis and regeneration.

Claire Chesnier’s auroral projections, Pablo Davilà’s particle circumvolutions and obsidian eclipse, Jean-Charles Eustache’s celestial colors and Eva Nielsen’s fiery skies form a constellation of atmospheres that responds to the organic, vital or material metamorphoses of Elsa Sahal, Özlem Altın, Leylâ Gediz and Elif Erkan in a movement of transformation and regeneration of forms.

Claire Chesnier’s paintings are dawnings of abstraction, luminous apertures onto the unfolding of hazy spectrums. They have an upwards atmospheric thrust in their overt abstraction. Their verticality displays bodily proportions inherited from the artist’s previous background as a dancer and veers towards the horizontality of a tremolo, streaking the paintings with striations of chromatic gradients. You have to live with one of these paintings to grasp its power of modulation, from dawn to dusk, in sync with the arrhythmias of climate and tempo. The calendar entry comes across in the titles, indicating the day, month and year the painting was completed. Her paintings embody and connect to the world’s light through their chromatic versatility, their tendency to breed retinal persistence, to fluctuate, to vanish and reappear, to exude a halo. To view these paintings is to ride on the wings of duration and light in the clasp of incarnated painting, bringing new meaning to the notion of viewing: a revelation of the perceptible sensorial world, an endlessly reiterated focus, bedazzlement, lucidity, a sequence of clairvoyance, withdrawal, loss, recovery – the way sight is recovered after transient blindness.

Jean-Charles Eustache’s paintings are executed in acrylic on wood, with an extreme attention to the surface. His paintings, barely larger than the hand that gave them birth, offer a smooth, mat surface worthy of an Italian primitive with an unconditional passion for his expanses. His paintings are neither figurative nor abstract: they reflect a time dedicated to the observation of walls or façades caressed by sunlight, they also find their origins in the subtle colors used by painters of the past to render the hues of day and night in the thickness of air. We’re reminded of Giotto, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca and the tactility of the decorative geometric grisaille frescoes in Villa Poppaea, near Naples, in the 1st century. Light settles, duration stretches, as the sun’s flamboyance fades to its last candlestick flickers. The light, its modulations, have slowly revealed the stone’s reliefs and hollows, giving a chalk-like consistency to the surface, to the hours, to the elusive extinction of day, making the blueness of the surface blossom, the golden hour of evening, the vesper colors and the most impenetrable night.

Pablo Dàvila’s Phase Paintings (The natural flow of forgetting) are part of a series exploring the notions of time and movement, of movement in time. Every painting depicts two instances that when overlapped and translated into visual terms generate a third moment of difference, interference and disruption. The discrepancy of the image is none other than the visibility of time’s passing, and along with it, the memory, perception and the trace that it leaves behind. The image evidences both the presence and the absence of a representation within the span of a second. Commenting on the obsidiann circle Stories of nearly everything, Pablo Dàvila explains: « I started doing these sculptures after reading about an eclipse that occurred on May 29, 1919. That eclipse was quite important because it was used to test Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, specifically to test the idea that mass causes space to curve. Einstein’s general theory of relativity underlies our most basic modern cosmology, our way of looking at the universe as a whole. To me eclipses are special because they draw a lot of people to stare at the same spot in the sky at the same time, this gesture is very po-werful. In Mexican prehistoric cultures, obsidian was of the utmost importance as it was used in many different ways, especially as a shadow lens in order to watch eclipses without damaging the retina. »

The two paintings by Eva Nielsen place the landscape in a register that belongs more to the realm of memory than to strict representation. These two views, blazed by the setting sun, are veiled at the very moment they are unveiled to the eye. The first, pearled with fine droplets, seems to have prematurely received the morning’s dew. Its cloudy, opaque, grainy surface could also be that of a photograph distorted by the action of combustion. Clearly, the original image seems to have been taken from the window of a moving train speeding across the countryside, as attested by the overlapping reflections, in an impossible fixation of the landscape, in a blurred memory of what has been seen. The second painting offers a wrinkled surface, like an old photograph crumpled and then flattened, forgotten and then found again. In both works, the landscape seems to be an illusion fabricated by memory, impossible to reconstitute, folded, unfolded, until the effusions turn these expanses into the undecided zone of Eva Nielsen’s memories, opening up our own involuntary memory fields to the marvel of a landscape we might have once contemplated.

In The Colour Out of Space, Lovecraft describes how the unknown color, lodged in the heart of the meteorite, spreads and takes possession of its environment, removing its hues, like an image passed into simple gray values in a software program. Palette III by Leylâ Gediz is a painting named after the plate used by painters to mix their colors, but the graphic palette is also the designation given to software used to process and modify images. Palette III would therefore be both a painter’s palette - which it is not, since it is a finished painting - and an interface for transforming the appearance of things - which it is not either, since it is a finished, frozen painting. Palette III reveals the most primitive state of painting in the making, at the stage of project and interface, and simultaneously constitutes a still life whose subject would be painting as still life by definition, as mourning of the real in its inexorable tension towards ash-gray. We have to place ourselves in the painter’s position as she smears her surface with simple gestures mixing shades of grey with light shades of beige and yellow, accepting to put an end where there should only be a beginning, granting these few gestures the profound dramaturgy of a memento mori.

Özlem Altın’s large-scale panoramic painting Translucent Shield is a symphony dedicated to life, regeneration, fragility, to the invisible energy of fluids, to the universal forces that underpin the principle of life despite the precariousness of bodies, despite the perishable, despite everything that should stand in the way of vital outbursts and epiphanies. This virtuoso photographic collage, made up of images found or taken by the artist during the childbirth of one of her friends, composes a vast fresco in which fragmentary representations of birth, mutation and the passage from the aquatic matrix into the worldly air are interwoven. Twin figures, ritualized hand gestures like sacred impositions, avian and simian apparitions protecting their eggs and offspring, placentas, cellular forms and vegetal veins form a whole unified by the white ink that partially covers the images. Linking photography and painting according to an organic principle characteristic of Özlem Altın’s work, the milky white gives unity and strength to the whole, while at the same time marking the porcelain fragility of what is being represented. Life lies there, behind this translucent shield, always on the threshold of its possible annihilation, always fragile, and yet always beginning again, despite everything.

Elsa Sahal’s sculptures are emblematic of an art founded on a permanent hybridisation of forms. Pied (“foot”), for example, evokes an antediluvian colossus extracted from black clay during an archaeological excavation, a strange colossus whose burnt-stone roughness is set against the smooth perfection of an ovoid female form, itself coupled to an organic spinal column made of strata stacked in a tumulus and echoing the megalithic burial structure of a cairn. Masculine and feminine merge, mutating bodies and organs in subtle, eroticizing twists. The two works suspended by straps belong to the Léda series, inspired by the name of the woman whom Zeus seduced by taking on the appearance of a swan. Halfway between the tucked or coiled neck of a swan and the curves of an erotic organic form, these two sculptures place the eye on the threshold of the phenomenon of metamorphosis, where the upheaval of genres and forms is as much that of the extraordinary passage from human to animal as that of a contortionist violence wrought on unrecognizable organic elements. The ambivalence of the Leda myth has inspired artists throughout history, from Antique sculptors to Constantin Brancusi, from Leonardo da Vinci to Cy Twombly, in a constant vacillation between romantic representation and violence. Elsa Sahal’s sculptures turn them into entangled, deformed bodies, suspended and constrained by straps that place them halfway between the terrestrial and the aerial. The subtle enameling of the surface gives the two coiled bodies the fragility of porcelain, with white and bluish hues reminiscent of swans.

The title of Elif Erkan’s painting, In Bloom, evokes the springtime blossoming of flowers, renewal and regeneration. However, the rust-covered surface has gradually consumed the floral representation, creating a dramaturgy of still life and memento mori, leaving only a limited space for the flowers, whose luminous and decorative power is then multiplied. The painting depicts a “blasted heath”, to use Lovecraft’s term for a landscape eaten away by the color that has fallen from the sky. But this expanse, corroded by slow oxidation, paradoxically opens the representation to a form of magnificence. The starting point is a low-quality vernacular painting found by Elif Erkan, whose surface she has completely obstructed before scraping away a small area, uncovering a fragment of the original paint and revealing an unexpected ornamental power. The few touches of green, blue, red and yellow spared by the rust open up a space of intense light, an eyecup of beauty where a simple flower manages to illuminate the iron ochre.