Under one lamp by day, billions by night : Pablo Dávila

I sometimes think that nothing really is new; that the first pixels were particles of ochre clay, the bison rendered in just the resolution required. The bison still function perfectly, all these millennia later, and what screen in the world today shall we say that of in a decade? And yet the bison will be there for us, on whatever screens we have, carried out of the primal dark on some impulse we each have felt, as children, drawing. But carried nonetheless on this thing we have always been creating, this vast unlikely mechanism that carries memory in its interstices; this global, communal, prosthetic memory that we have been building since before we learned to build.

When we turn on the radio in a New York hotel room and hear Elvis singing “Heartbreak Hotel”, we are seldom struck by the peculiarity of our situation: that a dead man sings.

In the context of the longer life of the species, it is something that only just changed a moment ago. It is something new, and I sometimes feel that, yes, everything has changed. (This perpetual toggling between nothing being new, under the sun, and everything having very recently changed, absolutely, is perhaps the central driving tension of my work.)

Our “now” has become at once more unforgivingly brief and unprecedently elastic. The half-life of media-product grows shorter still, ‘til it threatens to vanish altogether, everting into some weird quantum logic of its own, the Warholian Fifteen Minutes becoming a quark-like blink. Yet once admitted to the culture’s consensus-pantheon, certain things seem destined to be with us for a very long time indeed. This is a function, in large part, of the rewind button. And we would all of us, to some extent, wish to be in heavy rotation.

And as this capacity for recall (and recommodification) grows more universal, history itself is seen to be even more obviously a construct, subject to revision. If it has been our business, as a species, to dam the flow of time through the creation and maintenance of mechanisms of external memory, what will we become when all these mechanisms, as they now seem intended ultimately to do, merge?

The end-point of human culture may well be a single moment of effectively endless duration, an infinite digital Now. But then, again, perhaps there is nothing new, in the end of all our beginnings, and the bison will be there, waiting for us.

William Gibson, Dead man speaks

-

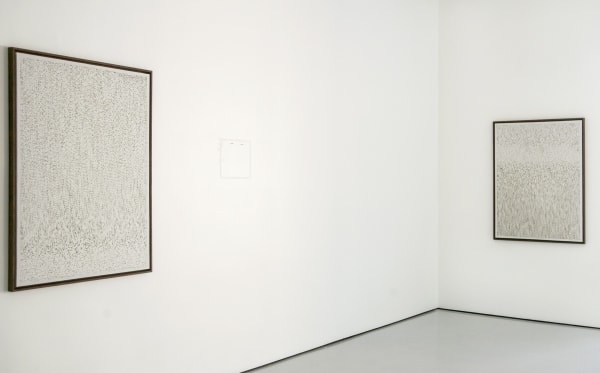

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting II, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting II, 2021 -

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting III, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting III, 2021 -

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting IV, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting IV, 2021 -

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting V, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting V, 2021 -

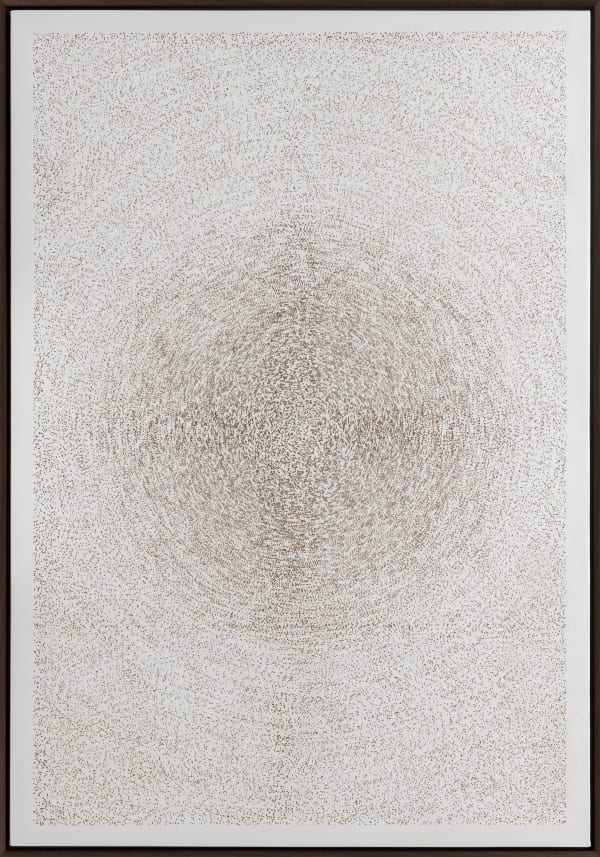

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting I, 2021

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting I, 2021 -

Pablo Dávila, FROM ME FLOWS WHAT YOU CALLTIME, 2019

Pablo Dávila, FROM ME FLOWS WHAT YOU CALLTIME, 2019 -

Pablo Dávila, ..AND SO JUST LIKE THAT IT KEEPS ON SPINNING

Pablo Dávila, ..AND SO JUST LIKE THAT IT KEEPS ON SPINNING -

Pablo Dávila, (288-1) Senza Replica

Pablo Dávila, (288-1) Senza Replica -

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting, 2019

Pablo Dávila, Phase Painting, 2019 -

Pablo Dávila, Let us go then

Pablo Dávila, Let us go then