Stagehand: Leylâ Gediz

Past exhibition

Press release

T H E P I L L ® is pleased to present Leylâ Gediz’s fourth solo exhibition at the gallery between 21 September — 16 November 2024. Titled Stagehand, the exhibition marks a new chapter in the artist’s research into support structures and processes usually held outside frames of representation, this time with a focus on theatrical production.

In theatre, a stagehand describes the profession of people who work backstage in various roles to set up the scenery, lights, sound, props, rigging, and special effects for a production. Each act in a play takes place within a specific "scene," which consists of a different set of scenery and props. The curtain conceals a flurry of activity between acts, as one world of painted backdrops, furniture, rigging, and props is replaced by a new one by stagehands during intermission, out of sight of the audience. As the story unfolds, the disappearance and reappearance of the backdrop that frames the play, the characters, and the action, attached to the wooden frames that hold its painted fabric, always occurs in secret. Unfolding through a series of large-scale paintings-as-assemblages that fragment and recompose archival images and support structures from theatre, Leylâ Gediz’s exhibition opens up a space of translation between the processes of painterly composition and those underlying a set change.

Leylâ Gediz approaches painting as a thought process and discursive practice to explore the relationship between figuration and its conditions of possibility. Her process-oriented practice incorporates fragments of everyday life filtered through contemporary image-processing technologies. Her paintings are structural experiments that dislocate and rearticulate the relationship between background and figure, simultaneously deconstructing painting into its constitutive materials and processes and rearticulating it through techniques of assemblage.

Leylâ Gediz (b. Istanbul, 1974) lives and works in Lisbon. She completed her MA in Visual Arts at Goldsmiths College (London, 1999) and a BA in Fine Art (Painting) at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL (London, 1998). Her recent solo exhibitions include “Home Staging” at CAC Cosmos (Lisbon, 2024); “Cosa Mentale”, Galerie L’Atlas invites THE PILL (Paris, 2022); “Layer From Background” supported by Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Edificio EPUL de Bartolomeu da Costa Cabral, Martim Moniz (Lisbon, 2022); “Denizens”, THE PILL (Istanbul, 2019); “ANAGRAM”, OJ Art Space (Istanbul, 2018). Her notable group exhibitions include “Painting Today”, cur. Didem Yazici & Burcu Cimen, Yapi Kredi Gallery (Istanbul, 2024); “This Play” cur. Emre Baykal, ARTER (Istanbul, 2022); “Hybridish” cur. Alistair Hicks, Georg Kargl Fine Arts (Vienna, 2020); “Words Are Very Unnecessary”, cur. Selen Ansen, ARTER (Istanbul, 2019); “The New Normal”, The Hangar (Beirut, 2017); Freundschaftsspiel Istanbul, Freiburg Museum Für Neue Kunst (Freiburg, 2016); “Every Inclusion Is An Exclusion of Other Possibilities”, SALT Beyoglu (Istanbul, 2015); “Skeptical Thoughts on Love” cur. Misal Adnan Yildiz, Künstlerhaus Stuttgart (Stuttgart, 2014); Istanbul Eindhoven-SALTVANAbbe: Post ‘89, SALT Beyoglu (Istanbul, 2012); “Dream and Reality - Modern and Contemporary Women Artists From Turkey”, Istanbul Museum of Modern Art (Istanbul, 2011). Leylâ Gediz’ work is included in prestigious public and private collections such as Istanbul Modern, Arter (Istanbul), ARCO Foundation (Spain) and Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven). In 2023 she was the recipient of the Sovereign Portuguese Art Prize by public votes.

Installation Views

Works

Exhibition Text

Looking for Poetry in Wastelands

Words and objects in the work of Leylâ Gediz

By Jennifer Higgie

2nd draft 20 June 2024

In 2023, Leylâ Gediz staged a solo exhibition in London of paintings titled 'Missing Cat'. In 2024, she returned to the subject with Kayıp Kedi (Missing Cat): a black and white oil on linen work of a large mottled feline floating amid two blocks of Turkish text, alongside a phone number with a Portuguese code. Both the exhibition and the painting are based on a poster that Gediz, who is Turkish, came across on the streets of Lisbon, where she lives. Prompted by the rising number of Turks who have left their country because of economic hardship and political repression, the artist reworked the missing cat notice into a poster that communicated confused data - it features a cat that is both physically lost and lost in translation. Although she talks about the work as something of a joke, her gesture also reflects something serious: 'the attempt to translate my impressions into a language' and also 'the impossibility of translation'. She explains: 'I am very much drawn to things that don't work or can't work no matter how much you try.'

As someone who was born and grew up in Istanbul, schooled in German, studied in London and moved to Lisbon, translation has long been something that Gediz has had to grapple with. Perhaps inevitably, the challenges of shifting meaning from one language to another would preoccupy her. In her work - which comprises painting, drawing, installation, photography, video, sculpture, performance - she honours slippages, fragments and glimpses by homing in on the overlooked and the underappreciated. Gediz explores the world and her place in it from myriad angles, highlighting the gulf between intention and actuality that each of us experiences, to varying degrees, daily. Trying to pin her work down to a single meaning is futile; its power lies in the near-theatrical accumulation of references that range from the idiosyncratic to the cultural. Like the character in Samuel Beckett's 1983 story Worstward Ho, whose credo is 'try again, fail again, fail better', her playful inventiveness makes clear how productive failure can be - and how new meanings and images can emerge from the wreckage of what once was.

When Gediz first sent me a pdf of her work, I asked her if the images I was looking at - which comprised a dizzying range of stylistic approaches, from abstract sculptures to figurative paintings, room dividers and poems - were part of a group show. She laughed, explained she was responsible for everything in the pdf and said:

When I was a student, there was a time when I even wondered if I should instead study curatorship because I needed to curate myself. I was interested in so many diverse things and my practice was, and is, inspired by collecting and bringing things together and trying to see how they might fit together or relate to one another.

Collecting is at the heart of Gediz's practice; she sees creative potential in the most humble of materials and believes 'there are stories behind everything'. Something of an archaeologist, she reflects upon the history of her neighbourhood, and her place in it, through its detritus. On her daily walks, Gediz searches for abandoned furniture, cardboard boxes, paper rolls, Styrofoam packaging and more. She hauls them back to her studio and spends hours reshaping or reassembling them; she often inserts herself into compositions, viewing herself in the role of 'a solitary actor or actress'. Over the years, she has variously pictured herself rolled up in sheets of cardboard, standing on a stool with a paper shield and wrapped in checked cloth. In 2024 she was included in a group exhibition 'Eu Estou Aqui' (I'm here): she photographed herself sitting in a cardboard box, gazing out with a wary expression; above her, it is her again, this time leaning on the box, she looks away. It's an image that combines loneliness and dark humour - the artist both hidden and revealing herself - in equal measure. The artist transformed the photograph into a large painting, Doll's House for the show: its title inflects the reading of the work into a longing for childhood that is countered by the often false protections it offers.

For her 2023 exhibition 'Missing Cat', Gediz photographed a cross-section of repurposed objects and then photoshopped, projected and painted them in monochromatic grey, white, brown and black tones. The result is a series of paintings that, from a distance, seem like hyperreal still lives but, up close, are more painterly; the artist's hand is very present in the soft blurring and wobbling of lines and tones. Paintings include an arrangement of rolls of shaped paper on a plinth (Troubleshooter, 2023); black and brown cardboard boxes, torn and assembled like the battered model of a modernist building (Erkete, The Lookout, 2019); and a yellow-gridded cutout - which was created for masking tape - of a cat that casts a doubled shadow on the wall (Cat, 2023). Still Life with Lampshade (2023) is a complex, semi-abstracted arrangement of checked patterns piled up and overlapping one another; in one section, a fringed, old-fashioned lampshade, like a ghost from an earlier era, can be glimpsed. One of the most enigmatic works is Rumpelstiltskin (2023), a doubled self-portrait in which the artist depicts herself in two poses, in black leggings and a dark jumper, one leg raised, holding a large, white shell-like object that could be the remnants of a chair. The clue to what she is doing is in the title. Rumpelstiltskin - a German fairy tale about longing and loss, deceit and redemption - concerns an imp who spins straw into gold to save a young woman from her father's deceit, and who, thwarted in his attempts to take her firstborn child as payment, pulls off his leg and hops off, howling: justice is done. As the English 19th century novelist Charles Dickens declared: 'in a utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that fairy tales should be respected.'

I ask Gediz what painting can add to a photographic image. She explains that whereas a photograph is taken in the blink of an eye, in the much slower process of becoming a painting, something unpredictable happens to the image. As areas are highlighted, compositions shifted and colour muted, a new picture emerges - and there can be magic in such a transformation. The artist describes this mutability as one 'of negotiation', that involves 'changing the costume of skin from a digital image to a paint surface'. She adds: 'My paintings come to being as the result of play.'

The reasons for Gediz's monochromatic choice of colour are complex. A few years ago she was making bright, colourful paintings, but more recently, after a diagnosis of ADHD, she decided she was 'employing too many tools'. She wanted to 'slow down her inner dialogue' and 'reduce the amount of noise' both visually and in her head, in order to 'be in the moment' and focus on how each of the objects in her compositions might relate to each other. However, Gediz's predominantly black-and-white palette also has another association: the written word - books, of course, are almost always black text on white paper. She explains:

I can only get the idea across in painting after many takes and always with considerable time in between, possibly because any application of paint is like using words to construct a text. I often get asked about colour in my painting […] My answer is, I see enough fluctuation on the surface as it is, I don't want to complicate things further by adding colour. There is no colour on the pages of a book, is there? I don't need so much colour to make my point in painting.

In the past few years, Gediz has been preoccupied by the question of how best to put a piece of writing into the world: as a result, she's created texts released from the confines of a book, transformed handwritten poems into paintings and performed them amid her exhibitions.

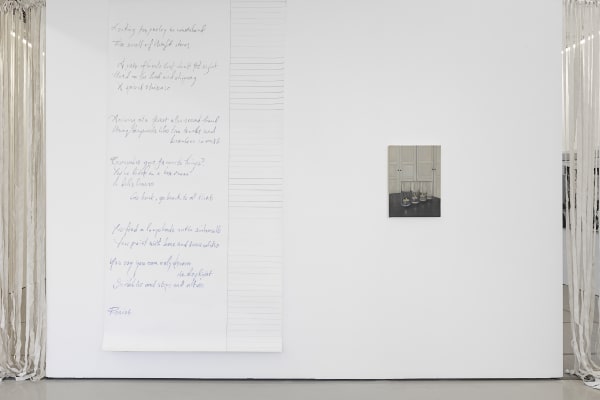

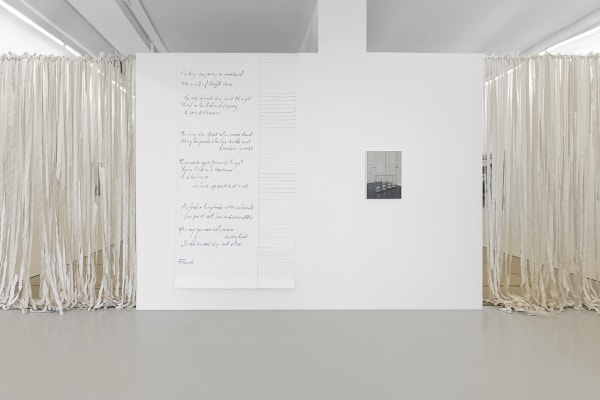

She wants her words to 'share the air' of the gallery with artworks and to 'make objects out sound'. She believes words are a vital component of an exhibition, the meta-narrative link that connects disparate objects. Styrofoam Dreaming (Resist) (2024), for example, which was shown in 'Eu Estou Aqui' (I'm here), is a two and a half metre long handwritten poem. Like glimpses of a landscape from the window of a speeding train, the poem's fragmented lines are a sensual evocation of place and mood, objects and atmosphere:

Looking for poetry in wasteland / The smell of thrift stores / A pair of boots that don't fit right / Hard on the heel and slippery / A spiral staircase / Arriving at a forest, also second hand / Using keywords like tree trunks / and branches in mist / Remember your favourite things? / You've lived in a box room / A doll's house / Go back, go back to all that / You find a lampshade out on the sidewalk / You paint with bone and snow whites. You say you can only dream in daylight / Scribbles and steps and altars / Resist.

A small still life painting, Silent Call (2024) of four glasses with tea lights was hung on the edge of the text. Two enigmatic sculptures added to the exhibition's mysterious atmosphere: Altar (2024) comprises a folded brown cardboard screen which forms a protective barrier behind a Buddha's head on a Styrofoam plinth; and Birthday Present (2024), a mysterious assemblage formed of a large wooden cable reel, a tripod, a ribbon and moulded polystyrene. The suggestion is one of a theatre set, with the viewer the actor who completes the scene.

Gediz's fascination with combining words and images has obvious parallels with the world of theatre, which the artist describes as 'crazy inspiring for painting'. It was apt, then, that she was invited to stage an exhibition in Lisbon at Cosmos (CAC) - the Athletic Club of Campolide - which was used as a refuge by radical theatre makers between 1970 and '76 during Portugal's fascist regime. Delving into the club archives, she found a treasure trove of photographs taken of the company rehearsing, which she used as a springboard to create the exhibition 'Curtain Call', which opened in March 2024. It included the ghostly Stage-Struck (2024) a two-metre, dream-like collaged drawing on what looks like a theatre set of actors, rehearsing; leaflets and photographs from the 1970s advertising the plays, a painting of a silhouetted woman in a long dress gesturing to the sky (Stunt Girl, 2024) and a spoken word performance.

Looking over Gediz's sculptures, paintings and texts, it becomes clear how images of breakage and repair weave in and out of her thinking. Artmaking is, for her, a therapeutic act, not just for the individual but for society. Again and again she resurrects old boxes into abject sculptures and paintings; takes photographs of posters peeling off a wall, treats discarded Styrofoam packing with the dignity of marble; paints a single broken egg, a fading receipt, sugar cubes, a broken marionette and an old can with attentive reverence. She tells me, with an expression of hope, that whilst coming across objects that are broken often makes her sad, it also triggers in her the impulse to do something reparative. She laughs, shakes her head and says: 'I realise it's an almost hopeless attempt to make something good again. To fix it.' It's clear, though, that very little will stop her from trying.

About Jennifer Higgie

Jennifer Higgie is an Australian writer who lives in London. She was frieze magazine reviews editor from 1998-2003; co-editor with Jörg Heiser and then Dan Fox until 2017; frieze editorial director from 2017-19 and editor-at-large until 2021. She is the presenter of Bow Down, a podcast about women in art history; the author and illustrator of the children's book There's Not One; the editor of The Artist's Joke; author of the novel Bedlam; and the writer of the feature film I Really Hate My Job. In 2015, Higgie curated the Hayward Touring and Arts Council Collection exhibition 'One Day, Something Happens: Pictures of People', which travelled from 2015-17 to Leeds Art Gallery; Nottingham Castle; Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda; The Atkinson, Southport; and Towner Gallery, Eastbourne. She has been a judge of the John Moore's Painting Prize, the Paul Hamlyn Award, the Turner Prize and the 2021 Freelands Painting Prize and a member of the advisory boards of Arts Council England, the British Council Venice Biennale Commission and the Contemporary Art Society. She is currently on the Imperial War Museum Art Commissions Committee.

Jennifer Higgie is the inaugural editor of the National Gallery of Australia's new publication The Annual and the host of the NGA's new podcast Artists's Artists. In July 2023, the exhibition she curated, 'Thin Skin' - a survey of contemporary and historical painting - opened at the Monash University Museum of Art in Melbourne. (Read Ocula editor Anna Dickie's interview with Jennifer about the show here.) She is also currently working on various scripts. Jennifer Higgie holds a BA Fine Art (Painting) from the Canberra School of Art, and a MA (Fine Art, Painting) from Victoria College of the Arts, Melbourne; her paintings are in various public and private collections in Australia. She travelled to London on a Murdoch Fellowship in 1995 and stayed.

Press