ISLAWIO: Apolonia Sokol

Passé exhibition

Communiqué de presse

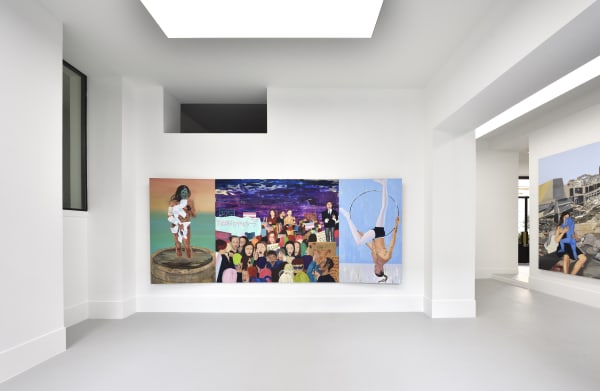

T H E P I L L® est heureuse d’inaugurer son installation à Paris avec l’exposition solo très attendue d’Apolonia Sokol, ISLAWIO, qui ouvrira le 15 octobre 2024 à la nouvelle adresse de la galerie, au 4, place de Valois.

Cette première exposition monographique d’Apolonia Sokol en France, intitulée d’après l’acronyme d’un vers de la poétesse américaine Audre Lorde, I Shall Love Again When I’m Obsolete, réunit un ensemble de nouvelles peintures de Sokol marquant le moment présent et une compréhension du monde que nous habitons actuellement dans la longue histoire de la mémoire iconographique et des émotions véhiculées par la peinture. Son œuvre de grande envergure intitulée Le Massacre des Innocents est à première vue une réinterprétation du Guernica de Picasso avec sa représentation de membres sans vie et de parties de corps émergeant d’un tas de décombres, lui-même encadré par un paysage de désolation, mais elle fait également référence à des représentations moins connues de la guerre et de ses effets dévastateurs sur la vie et la psyché humaine, telles que A Mother and Her Dead Child (1949) d’Andrzej Wróblewski, ou The Apotheosis of War de Vassili Verechtchaguine (1871). La relation insidieuse entre la violence et le consentement est au cœur de Consentement, qui prend la forme d’un autoportrait de Suzanne, face au spectateur, son corps ouvert dans un champ d’herbe sous les symboles du regard masculin et du patriarcat. À l’instar de la poésie d’Audre Lorde, la colère puissante et exaltante qui jaillit de ces peintures trouve un contrepoids dans Transsupport, conçue comme un retable avec des représentations de l’atelier de l’artiste représentant ses collaboratrices, collaborateurs et amis, liés par l’amour et le chagrin, s’entourant les uns les autres, et le processus de la peinture comme un processus de guérison. Dans la pièce centrale tumultueuse représentant une manifestation pour les droits des transgenres, l’action collective et la manifestation publique deviennent des activités de soin et de guérison : ce qui est révélé est également guéri.

La soirée d’ouverture accueillera une série de performances d’Azzedine Saleck, Dina El Kaisy Friemuth, Noah Umur Kanber et un invité surprise, sous la forme d’un tutoriel de maquillage, d’une lecture et d’une performance interactive. Le documentaire primé de Lea Glob, Apolonia, Apolonia, sera projeté en parallèle au sous-sol de la galerie.

Vues de l'exposition

Œuvres

Exhibition Text

ISLAWIO

By Didier Semin

A short while ago, I was talking to a friend more or less my age (say who turned 15 in 1970) about the Kinks, a wonderful British pop band whose reputation has eroded over time: he was not far from placing their music above that of the Beatles or the Stones. Unable as I am to decipher sheet music, I did not argue, but to back up his assertion, he asked me if I knew the lyrics of Lola, a major hit by the Kinks in the year we turned 15. I’d never listened to them at the time, my school English was not good enough, and I only remembered that the first name Lola rhymed with Coca Cola. But they are, in fact, extraordinary:

“Well, I’m not the world’s most physical guy

But when she squeezed me tight, she nearly broke my spine

Oh, my Lola

[...]

Well, I’m not dumb, but I can’t understand

Why she walks like a woman and talks like a man

Oh, my Lola

[...]

Girls will be boys and boys will be girls

It’s a mixed up, muddled up, shook up world

Except for Lola

[...].

So one of the best-selling songs in the world half a century ago tells of a young man’s love at first sight for a trans beauty... The song should be forced to be listened to by the countless people who today describe gender transition as a new and deleterious phenomenon ruining our civilization.

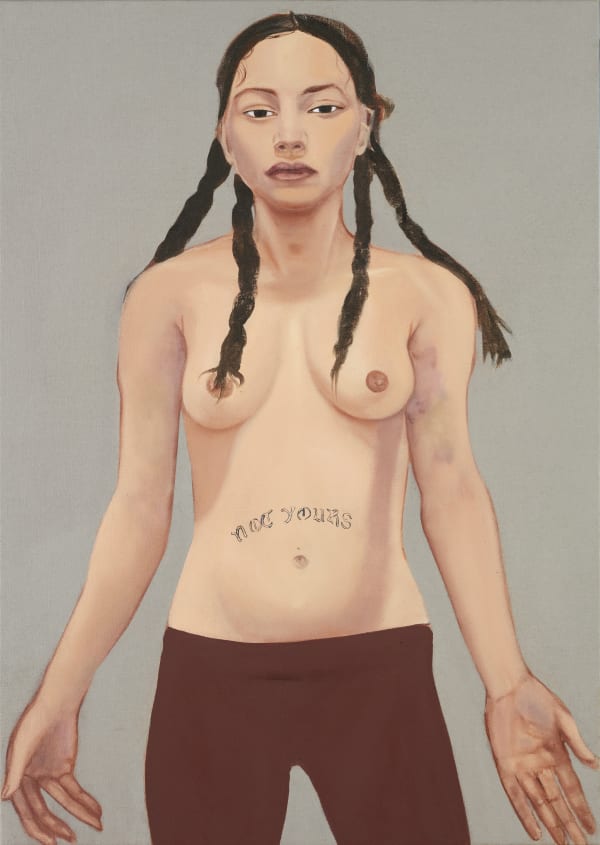

But: what are you talking about ? Quite simply, that nobody would ever consider the Kinks as a committed band -– and that it would be equally absurd to regard Apolonia Sokol’s painting, because it often celebrates trans-identity and feminist solidarity, as committed art - i.e. art dictated by an ideological agenda. Truth is, Apolonia Sokol simply paints the world in which she lives (as Nan Goldin once photographed hers in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency). In this world, to put it as she would, “nothing’s okay”: the democracies that still deserve the name are scarce, five women die every hour assassinated by their partner, the earth is warming dangerously, war is raging in the Middle East, Africa and Europe - the list is long, and, alas, familiar to everyone. Billions of images of a universe gone mad circulate at all times, on phones called “smart”, and one might ask why it’s still legitimate to paint it. However, since Baudelaire, we know that “the shape of a city changes faster [...] than the heart of a mortal” , and that no artificial intelligence has yet replaced the understanding of reality that we can obtain holding a pencil or a brush: painting addresses the heart of mortals, which hardly changed since the Renaissance, beyond the terrifying contemporary shape of cities. Apolonia Sokol renders what happens to her (to us) in the long history of emotions, as they were patiently recorded by artists over the centuries. Her Massacre des Innocents is obviously a reworking of Picasso’s Guernica, to which the lifeless limbs emerging from a pile of rubble are a direct reference, but it also includes quotations from paintings that, while lesser well-known, are no less moving: A Mother and Her Dead Child, by Andrzej Wróblewski (the painting dates from 1949), or The Apotheosis of War, by Vassili Verechtchaguine (1871). Like the artists of New Objectivity (or Magic Realism, Franz Roh’s beautiful expression that disappeared in French literature) in Germany in the 1920s and 30s, Apolonia Sokol integrates into her canvases the iconographic schemes that have long shaped our memory - My Operation is, in fact, a direct homage to The Operation painted by Schad in 1929, which reinterpreted Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson. She depicts herself as Susanna, exposed to the male gaze of old men (Consent). Her friends (often her assistants, as Apolonia’s studio is logically organized as during the Quattrocento, with assistants and students learning a craft that could only be learned through practice) become Christ-like figures, lifting their frames or paintings as if on a redemptive Way of the Cross (portraits of Anja Milenkovic and Camille Cecilia Tavares), or bearing the scars of mistreatmenting inflicted during an arrest (Not Yours, portrait of Dina El Kaisy Friemuth – Berlin artist arrested during a protest march). Matthias Garcia, also a painter, is depicted upside down, hanging from a hoop, showing that the Fortune wheel is, allegorically, turning the wrong way. Apolonia Sokol, it’s her dignity and virtue, doesn’t paint those she loves as she wants, but as they want, and willingly lets her assistants express their own style, when it contrasts harmoniously with hers. Emma Da Silva Rodrigues, for example, has painted, in her own way, the meadow where Suzanne-Sokol lies at the mercy of the old men! Consent also applies to painting: Jehane Mahmoud’s Birthgiving, a magnificent image of a birth like an Eucharist, was painted with the full agreement, and even complicity, of one of the artist’s former classmates at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris - she is a photographer - who, for the first time, was giving birth. (One day, we’ll have to seriously ask ourselves why painting, which has so abundantly depicted death in all its forms, has so rarely focused on childbirth: if we leave aside the primitive arts, for whom childbirth is not taboo, very few exceptions confirm the rule). The title of Apolonia Sokol’s exhibition at The Pill gallery, ISLAWIO, seems like the name of an imaginary country, perhaps the artists’ homeland: in fact, it’s the acronym of a verse by the great American poet Audre Lorde (can there be anything like the acronym of a poem? Yes, in Apolonia Sokol’s world, where the ugly face of modernity looks into the mirror of grace), I shall Love again when I’m obsolete. The significance of this can be understood if we recall what the artist tells in a remarkable documentary about her by filmmaker Lea Glob: hospitalized for a long time for a serious illness during her childhood, she was given religious books by the nurses, Catholic nuns, which is how she discovered painting – a few images that may well have saved her. That’s why her paintings are neither committed art, nor art for art’s sake, but holy pictures. Holy pictures for nightclubs and street demonstrations, secular gathering places where the sacred, which doesn’t like to be assigned to a place, has taken refuge.

Presse

-

Vogue France

Rencontre avec Apolonia SokolNovembre 12, 2024 This link opens in a new tab. -

Le Monde

Séléction galerie: Apolonia Sokol chez THE PILLNovembre 10, 2024 This link opens in a new tab. -

The Steidz

The Pill ouvre à Paris avec Apolonia SokolChirine Hammouch, Novembre 4, 2024 This link opens in a new tab.

Videos